Debugging and Testing

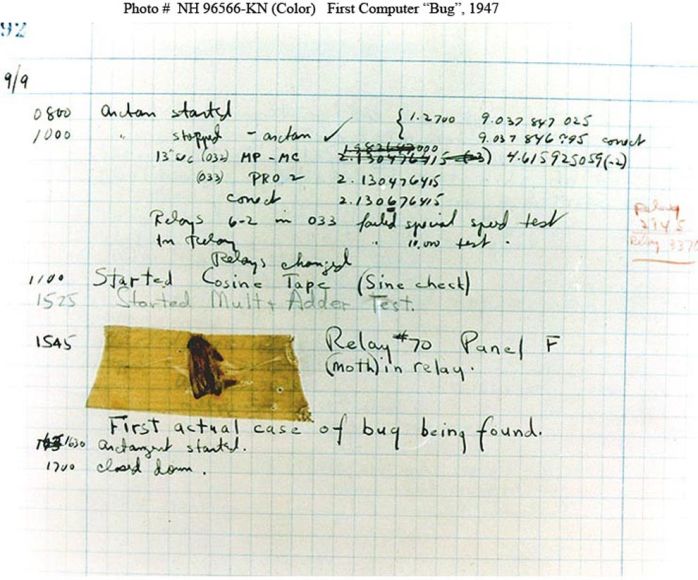

As programs get complicated, we stumble upon more and more errors or in programming terms: bugs. It was first coined by U.S. Navy Rear Admiral Grace Hopper when they found a moth inside their computer that caused issues with their calculations.

Bugs are always prone to appear in code and as programmers we must have systematic methods to prevent bugs from happening in the first place, test our code for bugs, and find the root of problems when we find them so we can fix and get rid of bugs.

Debugging

There are quite a few techniques that help find errors and that is usually the hardest part. Once the error is location, there is usually an obvious method to fixing the issue. To even find errors, we must be patient and systematic with our approach. There are a good few commonly used practices that make this process easier but they are not set rules. Instead they are guides which all provide a systematic way to approach the error at hand.

To begin debugging, we want to start with our complier because when an error occurs, it usually gives good feedback to you usually with the type of error it is, so to become better debuggers, we should understand what some of these errors mean.

| Error Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| IndexError | Access beyond the limits of a list |

| TypeError | Try to convert to an inappropirate type |

| NameError | Referencing a non-existent variable |

| TypeError | Mixing data types without appropriate cohesion |

| SyntaxError | Forgetting to close paranthesis, quotations, etc. |

| ValueError | Operand type okay, but value is illegal |

| IOError | IO system reports malfunction (e.g. file not found) |

| AttributeError | Attribute reference fails |

These error messages are sent by the complier and are very useful for locating the bug at hand.

Logic Errors

Typically the errors programmers spend more time debugging are logic errors compared to errors given by the compliers. Errors given by the compliers are nice because it is more obvious your code doesn't work because the program stops working and there is an indicator to where the error is due to the error statement provided by the complier. Logic errors are different because your code "works" meaning there are no rules Python has that are broken but the issue is you got an output that you did not expect. It takes quite a bit of time finding out why that is the case and sometimes those errors are not noticed till the program is used immensely more.

# Print if the integer is positive or negative.

def printPos(int n) {

if n > 0:

print('Positive')

else:

print('Negative')

}

# This program works but what if you give it a zero.

# Zero is neither negative or positive and this code doesn't catch that

def printPos(int n) {

if n > 0:

print('Positive')

elif n < 0:

print('Negative')

else:

print('Zero')

}

The example above is trivial but showcases how there may be values that the programmer may have not considered that could cause the output to be wrong. Larger programs mean there are more lines of code that could cause the unexpected output.

Methods of Debugging

- Use

printstatements to test hypothesises and see if variables have the values you want them to have. - Use the bisection method where you keep printing halfway through the code with the error to narrow down the problem.

- Study the code and ask how the unexpected error was obtained.

- Use the scientific method which means study the data, form hypothesis, repeat experients, and pick the simpliest inputs to test with.

- Draw pictures to better understand the code.

- Take breaks, sometimes a new fresh mind can help solve the issue.

- Use the rubber duck debugging method where you explain your code to a rubber duck or someone who does not understand coding so that you have to explain every bit of your code which helps really think about your own logic and can help you figure out where you logic went wrong.

Testing

There can be errors that are sitting latent in your code and to be able to find those errors, you need to test your code often. This is the process of comparing input and output pairs to specifications in order to break the program.

There are three levels of testing...

- Unit Testing are tests for each function and so each piece of the program is tested individually and made sure that it works.

- Regression Testing is the concept of adding tests for bugs that have already been found and fixed to avoid the resurfacing of bugs.

- Integration Testing is a bigger scope test where you are making sure the overall program works.

Creating Tests

To test code, intuitively you must test all the edge cases of your program and if there are no defined edge cases then the next best solution is random testing with random inputs. Of course with random inputs, the more inputs you try that work indicates that your program has a higher probability of not being buggy.

The two types of testing are black box testing and glass box testing. Black box testing is where you ignore the underlying code and only thing about the objectives or specification of the program instead of the underlying code. If the code has to turn the screen red when I press a button, that is what we test without worrying about how the code did it. The other type of testing is the glass box testing where you directly test every possible path that the code can take. Code has paths created when you start using control flow structure like loops and conditionals and every possible case of those need to be checked and verified to work properly.

You should do a mix of both tests but these are the distinctions we make when creating tests.

Defensive programming

So far we have looked at how to fix code, but it is also important to figure out ways to code in order to prevent a good handful of bugs from occuring ahead of time. Defensive programming cannot help prevent all bugs but can help make it easier to debug later and give you a way to cause less errors.

Defensive programming begins by writing specfications for functions and modularizing programs so that it is easier to debug each seperate section. After that you check conditions on input / ouputs.

When writing bigger programs, it is vital to break the code down into modular functions because it is easier to debug but you should always backup code as well. This is important because you can compare the working version of a code vs a code that caused the bug which immensely helps with debugging.

Assertions

You want to be sure that the assumptions are as expected so you can assert your conditions which verifies that your assumptions are met and if they aren't it raises an AssertionError.

# This function expects a non empty list

def first_element(arr):

# Asserts the list is not empty

assert len(arr) != 0, 'The list is empty'

# The error if caused will print

# AssertionError: The list is empty

# in the console

Assertions ensure that the programmer is only receiving data that they are expecting reducing bugs from bad inputs and bad outputs. You can assert to verify both the input and output are as expected making it easier to find bugs.

Exceptions

Besides asserting inputs / outputs, we can also raise exceptions which means we can print out our own errors. The syntax is raise <ExceptionName>(<arguments>) where the exception name classifies the type of error and the arguments can accept a string which is a message to be printed along side the error.

# Look at types of errors in the table above

raise ValueError("Something is wrong with the value")

raise TypeError("Wrong type was given")

# General exception

raise Exception("General error")

Besides raising errors, we can also catch them. Exceptions and assertions currently halt the program but we can catch an exception if we have a way to resolve it.

try:

# This is the code that is tried looking for errors

grades[1] = 2

except Exception:

# This code runs if any error is found in order to fix it

# Code continues running after this line

grades = [0, 2]

# Typically it is better practice to specify the type of error you are trying to catch

try:

# Code goes here

except ValueError:

# This only catches value errors

except IOError:

# You can have as many excepts as you want for a try.

These try and catch blocks give you plenty of versatility when it comes to resolving errors. They implement even more functionality through the use of else and finally.

try:

grades[1] = 2

except:

grades = [0, 2]

# This block only runs if there were no errors found in the try block

else:

print("No Errors Hooray!")

try:

grades[1] = 2

return grades

except:

grades = [0, 2]

return grades

finally:

# Even through code after a return should not run, finally runs no matter what

# Even if break, continue, or return are used

# Useful for cleaning up code

print("Returned successfully")

Assertions and exceptions allow for more control over issues that may break the code and help prevent it ahead of time. Debugging is a long process but with the right tools, solving these problems can be done faster and more effectively.