Generative Recursion

So far we have worked with structural recursion which is where each recursive call is made using a subset of the original data. This means the subset will eventually reach the base case. On the other hand, we will look at a new type of recursion called generative recursion which makes a recursive call made on data that was computed from the original data.

Function

Before we can look at generative recursion in action, we have a template we can use to solve generative recursion problems.

(define (genrec-fn d)

(if (trivial? d)

(trivial-answer d)

(... d

(genrec-fn (next-problem d)))))

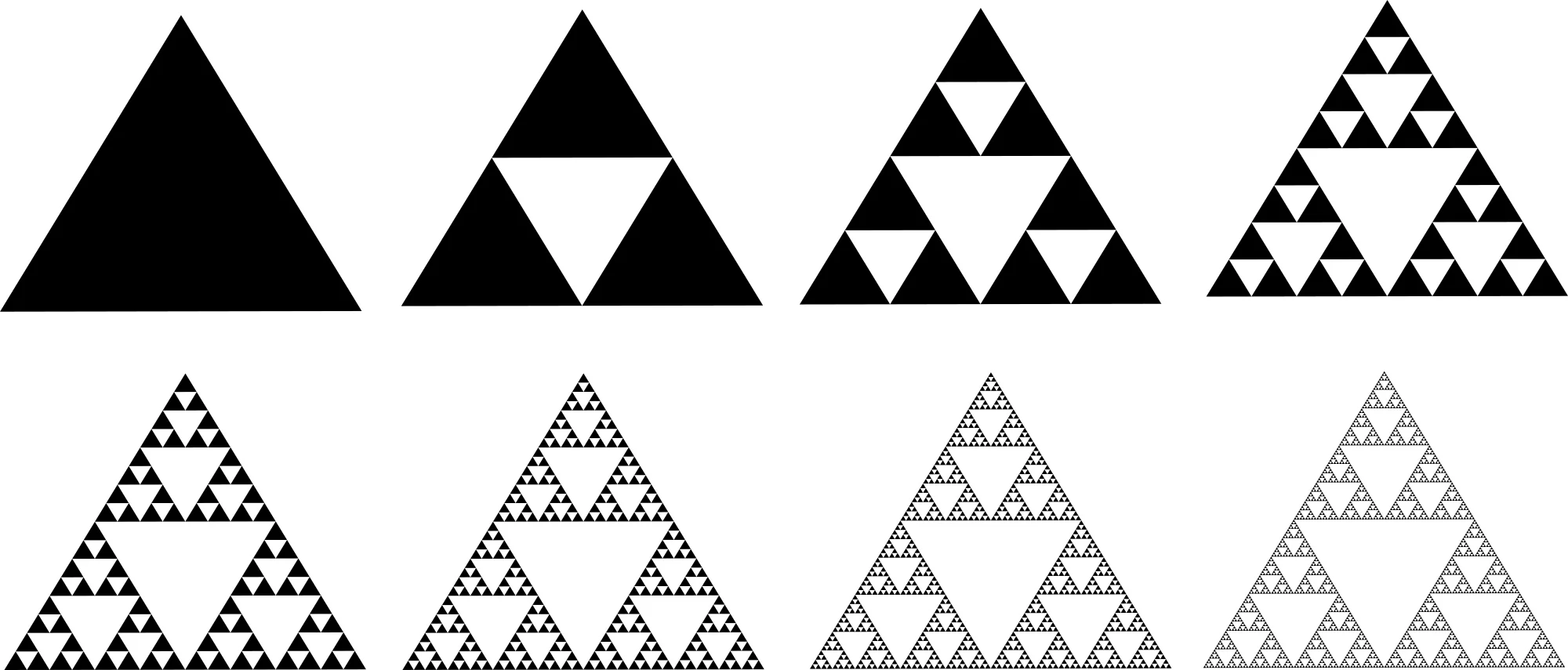

Sierpinski Triangle

One way to use generative recursion is to create fractals because in each recursive call, the fractal will get bigger which means it will get more complex and for each call, the data is compounded from the original.

For the function, our input is going to be a number that returns an image. There is no subset to a number which is fine because generative recursion just needs to use the input to find the next one no matter the data.

; This is the size of the simplest fractal

(define CUTOFF 2)

;; Number -> Image

;; produce a Sierpinski Triangle of the given size

(define (stri s)

(square 0 "solid" "white")) ; stub

For the tests, we only need to test the simplest case of the fractal and one case above that because that means the generative recursion can handle the rest of the cases. This is due to the fact all the cases are built upon the first two cases.

In the easiest case, we have an equilateral triangle with side length s. In the second case, we have three more sierpinski triangles. To built every other case, we place three triangles inside each of those.

(check-expect (stri CUTOFF)

(triangle CUTOFF "outline" "red"))

(check-expect (stri (* CUTOFF 2))

(overlay (triangle (* 2 CUTOFF) "outline" "red")

(local [(define sub (triangle CUTOFF "outline" "red"))]

(above sub

(beside sub sub)))))

Now that we have everything, we can use the template to create the function. Our trivial case is when the size is the same size as the CUTOFF.

(define (stri s)

(if (<= s CUTOFF)

(triangle s "outline" "red")

(overlay (triangle s "outline" "red")

(local [(define sub (stri (/ s 2)))]

(above sub

(beside sub sub))))))

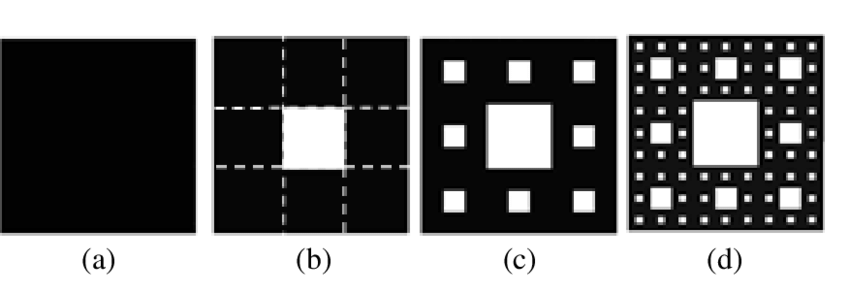

Sierpinski Carpet

Typically all fractals can be created using generative recursion so we will look at another fractal called sierpinski's carpet. This is where we take a square and cut it into 9 equal sized smaller squares and remove the central smaller square. We repeat this process for as many recursive calls as it takes.

Just like the last fractal, we have a CUTOFF size to dictate when this recursion has ended. One thing to also note is that in the triangle, for each recursive call, the size was halfed. For the carpet we need to cut the size into thirds because we are fitting 3 squares in each row.

;; Number -> Image

;; produce Sierpinski carpet of given size

#;

(define (scarpet s)

(square 0 "solid" "white")) ; stub

(check-expect (scarpet CUTOFF)

(square CUTOFF "outline" "red"))

(check-expect (scarpet (* CUTOFF 3))

(overlay (square (* CUTOFF 3) "outline" "red")

(local [(define sub (square CUTOFF "outline" "red"))

(define blk (square CUTOFF "solid" "white"))]

(above (beside sub sub sub)

(beside sub blk sub)

(beside sub sub sub)))))

(define (scarpet s)

(if (<= s CUTOFF)

(square s "outline" "red")

(overlay (square s "outline" "red")

(local [(define sub (scarpet (/ s 3)))

(define blk (square (/ s 3) "solid" "white"))]

(above (beside sub sub sub)

(beside sub blk sub)

(beside sub sub sub))))))

Termination

With structural recursion, the data sent to the recursive call is a subset of the original data so we can confidently say that eventually we will reach the simpliest case like how with lists, the simpliest case is empty.

The issue with generative recursion is that it keeps compounding the data meaning we can't always confidently state that the recursion will end. This means we need to verify that the recursion will end. We can verify this using a termination argument where we check the base case and reduction step which we use to argue that the recursion will terminate.

Termination Argument for Sierpinski Triangle:

Base case: (<= s CUTOFF)

Reduction step: (/ s 2)

Argument that repeated application of reduction step will eventually

reach the base case: As long as the cutoff is > 0 and s starts >= 0 repeated

division by 2 will eventually be less than cutoff.

===================================================

Termination Argument for Sierpinski Carpet:

Base case: (<= s CUTOFF)

Reduction step: (/ s 3)

Argument that repeated application of reduction step will eventually

reach the base case: As long as the cutoff is > 0 and s starts >= 0 repeated

division by 3 will eventually be less than cutoff.

Hailstone Problem

For the fractals, it was easy to argue that those recursions would end. There will be cases where it will be more difficult to argue and at some points even impossible. One case of impossible is with the Collatz Conjecture which states this process will eventually reach the number 1, regardless of which positive integer is chosen initially.

;; Integer[>=1] -> (listof Integer[>=1])

;; produce hailstone sequence for n

(check-expect (hailstones 1) (list 1))

(check-expect (hailstones 2) (list 2 1))

(check-expect (hailstones 4) (list 4 2 1))

(check-expect (hailstones 5) (list 5 16 8 4 2 1))

(define (hailstones n)

(if (= n 1)

(list 1)

(cons n

(if (even? n)

(hailstones (/ n 2))

(hailstones (add1 (* n 3)))))))

=================================================

Termination Argument for Hailstone Function:

Base case: (= n 1)

Reduction step:

if n is even (/ n 2)

if n is odd (+ 1 (* n 3))

Argument that repeated application of reduction step will eventually

reach the base case: This conjecture has never been proven so

we just have to trust it always ends.